Have you ever heard of a pregnancy test, HIV test, or a rapid COVID test? If yes, then you have already heard about the ELISA, or the Enzyme-Linked ImmunoSorbent Assay. The ELISA is a highly sensitive technique that uses antibodies to detect the presence of specific molecules (i.e. peptides, proteins, and hormones) in complex samples. Because of its low cost and ease of use, researchers use ELISAs in many fields, including medical diagnostics, forensic science, and in quality control of foods. We’ve developed some for the laboratory that you can perform with your students — but first, let’s learn about the history of this assay and the important components to perform the ELISA.

THE HISTORY OF THE ELISA

In the 1890s, researchers identified that serum from animals that had been immunized against diphtheria or tetanus could confer resistance to the disease when transferred into a second animal. The hypothesis was that there was a molecule within the serum that could neutralize a foreign antigen. They called this molecule an antibody (Ab) or an immunoglobulin (Ig). Through careful experimentation, researchers learned that antibodies are specialized protein complexes that allow the immune system to distinguish between molecules that are either “self” and “non-self.” Each antibody is highly specific and only recognizes one epitope (a particular location within a foreign substance). These foreign molecules were named antibody generators, or antigens. Once bound, antibodies mark antigens for attack by other parts of the immune system.

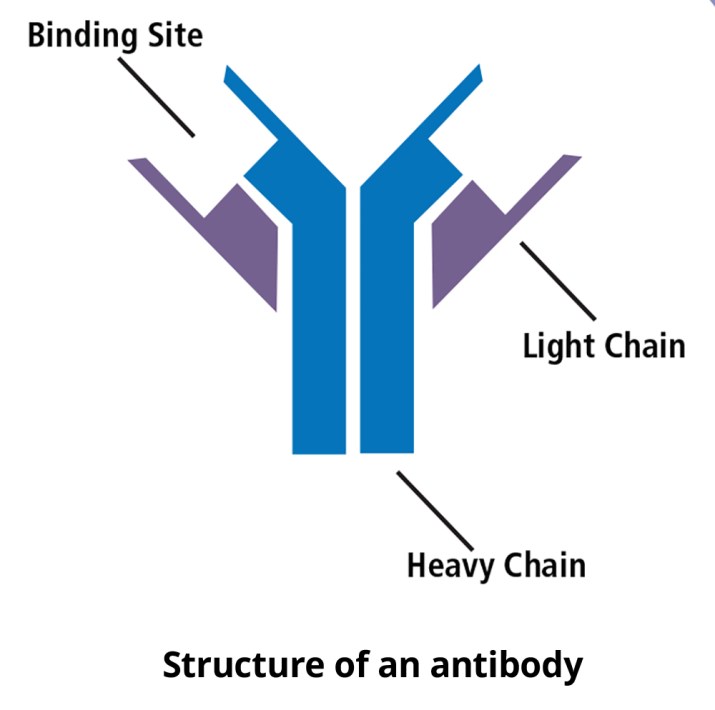

Each antibody is a y-shaped molecule composed of four polypeptide chains: two “heavy chains” and two “light chains”. The polypeptides are linked together by disulfide bonds. The vast majority of the amino acid sequence is the same if we compare antibodies that recognize different antigens. The differences lie in the amino acid sequence of the antigen-binding site (the little pocket at the end of the Y), allowing each antibody to recognize a unique antigen. Since the sequence can be so variable, antibodies can recognize a lot of different molecules.

Due to their specificity, scientists imagined using antibodies as powerful tools to detect specific molecules in biological samples. In the early 1960s, Rosalyn Yalow and Solomon Berson developed an assay that used radioactivity to detect the interactions between antibodies and their target molecules. This assay, called the radioimmunoassay, or RIA, lead to the ability for researchers to calculate the concentrations of antigens in solutions (like insulin in blood).

While this test revolutionized medical research, high levels of radioactivity can be hazardous to human health. In 1971, Peter Perlmann and Eva Engvall in Sweden, and Anton Schuurs and Bauke van Weemen in the Netherlands, independently linked antibodies to enzymes so that they could use colors (chromogenic reporter) or light (fluorescent reporter) to detect antigens. This innovation allowed researchers to quickly detect the smallest amount of antigen present in a sample without using radioactivity.

Since we can generate antibodies to lots of different molecules, the ELISA has been adapted for many uses. The ELISA is commonly used for medical diagnostics, as it is can be used to identify antigens in blood, saliva, urine and other biological samples.

PERFORMING AN ELISA

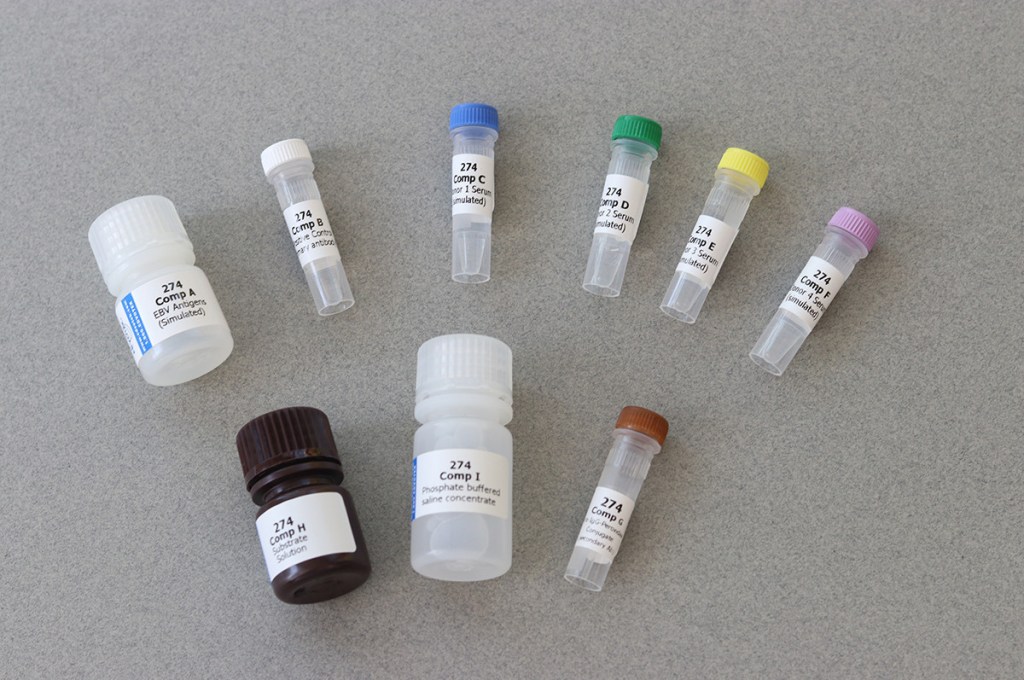

The following reagents are necessary to perform the ELISA.

- Test Samples: For many medical tests, this will be blood, or urine, or saliva from the patient. This experiment is a simulation – there are no live virus or human samples involved.

- Control Samples: These are lab prepared samples that we know how the assay should react. A positive control will give a positive result, and a negative control a negative result. If our controls fail, or if our assay does not give the correct results, it lets us know the experiment is invalid.

- Primary Antibody: An antibody generated to recognize and bind directly to the antigen of interest. So, for a COVID test, we’re looking for antibodies to SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19.

- Enzyme-linked Secondary Antibody: this antibody binds to the primary antibody and lets us detects the presence of our antigen in patent samples. It is connected to an enzyme that turns over a particular substrate, producing either color or light, which we can visualize.

- Buffer. This is generally used to dilute antibodies and wash wells.

- Microtiter plate. This is a thin piece of plastic with multiple little wells, each of which will provide a separate mini test tube that is in parallel with the other reactions.

- Pipette: A lab device that allow us to transfer samples and reagents into the wells. There are a few ways we can do this. One is a plastic transfer pipet. The other is a micropipet, which is a precision tool used to make measurements of very small samples. To simplify today’s demonstration, I’m going to use the transfer pipets. So, we can run this experiment without any special equipment.

The basic ELISA follows a few simple steps:

- The sample is added to the wells of the microtiter plate, where it adheres to the plastic through hydrophobic and electrostatic interactions. If the sample includes antigens, they will adhere to the plate.

- After washing away any excess sample, the wells are “blocked” with a protein-containing buffer to prevent non-specific interactions.

- The primary antibody is added to the wells, where it recognizes the antigen and binds through electrostatic interactions. This forms the antibody-antigen complex. Excess antibody is washed out of the wells.

- The secondary antibody, which recognizes the primary antibody, is added to the wells. If the antibody-antigen complex has formed in the well, the secondary antibody remains in the well after washing. Before performing the experiment, the secondary antibody is covalently linked to an enzyme that allows us to detect the presence of the antibody-antigen complex.

- The substrate is added to all the wells where it reacts with the enzyme. It either produces color (chromogenic detection) or light (fluorogenic detection) in wells where there is antigen-antibody complex. Since each enzyme can quickly break down many substrate molecules into product, we can get results in a few minutes.

QUANTITATIVE AND QUALITATIVE ELISA

The results we get from performing the ELISA can be qualitative or quantitative. The qualitative ELISA gives us a Yes or No answer: Stronger signal than standard is positive, lesser signal is negative. One example of a qualitative ELISA that you may be familiar with is a pregnancy test. This at-home ELISA tests urine for the presence of hormone HCG, which is an indicator of pregnancy. When taken at the right time, a pregnancy test will give you a yes or no answer.

In the Qualitative ELISA, we compare results from unknown to results from samples of known concentration. A standard curve is created where each well has a known concentration of antigen. We then perform the ELISA on the test sample and see where the signal matches the standard. For example, the ELISA is often used to test for the presence of known allergens in food, like gluten. A quantitative ELISA would let us know the exact amount of gluten was present in the sample.

2 comments

Comments are closed.