They say a picture is worth a thousand words, but in the realm of biology, its value skyrockets even further.

We’ve all experienced those magical “aha” moments when a complex idea suddenly clicks into place while staring at a well-crafted illustration. A good figure can break through misunderstandings and illuminate perplexing concepts.

Figures also have the power to reveal subtle nuances that might otherwise go unmentioned. In the intricate tapestry of biological systems, a multitude of phenomena are at play. Figures help us grasp the big take-home points and can also highlight some smaller but equally amazing details.

In this blog post, we’re putting the spotlight on a widely circulating PCR image and taking a closer look at the details within!

The Image:

Some immediate take-home points:

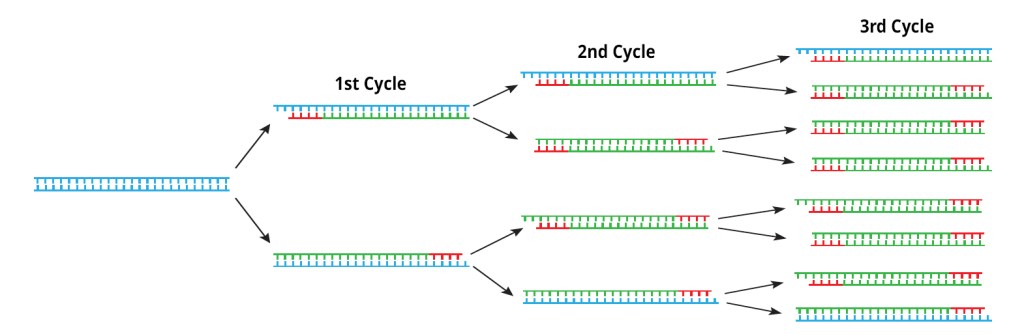

- The heart of PCR’s prowess lies in its cycles, which have the remarkable ability to exponentially amplify the quantity of DNA. This means that even if you start with a small sample of extracted DNA (containing only a few hundred DNA strands) these strands can quickly amplify to a mass of DNA visible to the human eye. With the image it’s easy to grasp this concept: on the right is the starting point of one single strand of DNA which by cycle three has been turned into eight strands. Now imagine what would happen after 25-35 cycles of amplification!

- Facilitating this cyclic amplification is the remarkable capability of both the initial DNA and the synthesized DNA to act as templates for subsequent strands. In other words, the freshly generated DNA in each round goes on to serve as a template in the subsequent cycle of synthesis. The image effectively illustrates this by coloring the original DNA blue and the synthesized DNA green.

- Primers play a critical role in PCR and are needed in large amounts. In this picture, the primers are colored red and do a good job of illustrating three key primer attributes: their short size, their strategic placement flanking the target region, and their ability to bind to DNA through complementary base pairing.

Likely the above three points jumped out at you and our description might have felt like a quick checklist – “Yep, got that!” But now let’s dig deeper, take a closer look, and discover some amazing biological details that the artist has drawn in.

Fascinating finer points:

- In the final (right) column you’ll notice the eight DNA strands appear somewhat alike yet slightly distinct. In fact, there are six different DNA ends. That’s because during the first few cycles of PCR extension can continue past the target zone. This could be a tricky situation especially as one of the most popular post-PCR activities is electrophoresis which relies on length to differentiate and ID different DNA targets. Luckily as cycles continue more and more copies are made from synthetic strands that have both the correct start and stop points so that by the time a collection reaches the end of a PCR program the majority of amplicons are the correct length. In addition, polymerases can only incorporate a limited number of nucleotides per binding event before dissociating – a trait called processivity. The processivity of most taq polymerases is low making amplification of large DNA targets tricky but also guaranteeing that these initial ‘open-ended’ copies don’t go on forever.

- Even though a PCR reaction calls for pairs of primers that flank the target regions, these primers are parallel players – rather than interacting they each bind to their own particular strand of single-stranded. This is because the 5′ end of a primer binds to the 3′ end of a DNA strand. In the first cycle, you can see this clearly with the forward (front) primer attaching to the upper DNA strand and the reverse (back) primer attaching to the lower DNA strand.

Are these last two points advanced for someone just wrapping their heads around this amazing technology? You bet! Do they also highlight the incredible biology behind PCR and encourage deep thinking. That is also a sure bet. While it’s not something most teachers would put on an exam, these subtleties encourage and facilitate students to think about what is happening at the molecular level. Which after all is one of the major reasons to teach PCR and a key prerequisite for using and troubleshooting this powerful lab tool.

FYI for a great video of the image check out the NIH site.