Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) is a naturally occurring protein that emits a green light when exposed to certain wavelengths of light. It’s an important component in many of our experiments because of it’s biochemical properties, but more importantly, because it is amazing to create glowing green bacteria in the lab! In this blog post, we’ll talk more about how GFP was identified, how it is used in the lab, and the molecular biology of its production and purification.

What is GFP?

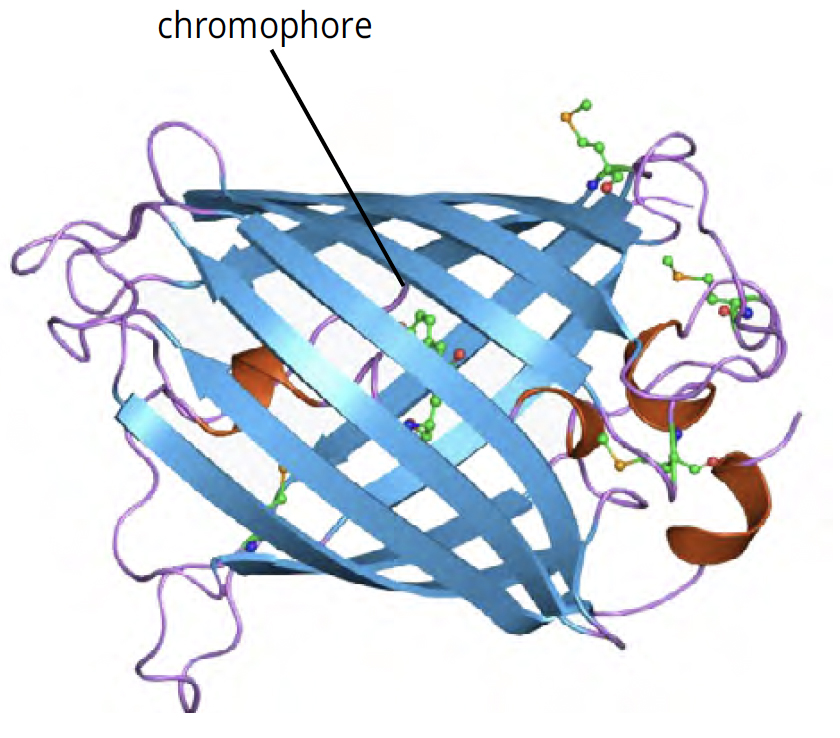

GFP is a small protein, approximately 27 kilodaltons in size. GFP possesses the ability to absorb blue light and emit green light in response. This activity, known as fluorescence, does not require any additional special substrates, gene products or cofactors to produce visible light. Instead, it is based on the beta-barrel structure of the protein and the location of its ‘chromophore’, a special structure within the protein that is responsible for light production (Figure 1).

How was GFP discovered?

Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) was discovered through the study of the jellyfish Aequorea victoria, which illuminates the eastern Pacific Ocean with its distinctive green fluorescence. The protein was isolated by the Shimomura lab in the 1970’s, but GFP only became a useful tool in the cell and molecular biology world once the gene was sequenced by the Chalfie lab in the mid-1990’s. Using this sequence, researchers used genetic engineering to develop a potent tool for cell and molecular biologists. Today, GFP is frequently used in research labs. Its ability to fluoresce without requiring additional cofactors or substrates makes it particularly useful for visualizing and tracking various biological processes within cells and organisms.

The Tsein lab took things one step further. They determined that sequence changes in the gene bring about different patterns of light absorption and emission, allowing scientists to develop a rainbow of fluorescent proteins (Figure 2). For example, GFP can be converted to BFP by making two amino acid substitutions, one of which is in the chromophore (His-Tyr). For their discovery and development of GFP and other fluorescent proteins, Osamu Shimomura, Martin Chalfie and Roger Tsien were awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2008.

Top: The gene is essentially turned off. There is no lactose to inhibit the repressor, so the repressor binds to the operator, which obstructs the RNA polymerase from binding to the promoter and making lactase.

Bottom: The gene is turned on. Lactose is inhibiting the repressor, allowing the RNA polymerase to bind with the promoter, and express the genes, which synthesize lactase. Eventually, the lactase will digest all of the lactose, until there is none to bind to the repressor. The repressor will then bind to the operator, stopping the manufacture of lactase.

T A RAJU, CC BY-SA 3.0

How do we express GFP in bacterial cells?

In the laboratory, we can engineer a plasmid that contains the DNA sequence for GFP. Once transformed into E. coli, this protein is expressed using an inducible promoter, making the bacteria glow bright green! Scientists can control the expression of recombinant proteins using inducible promoters, acting as genetic “on/off” switches triggered by specific molecules like arabinose, tetracycline, lactose, or IPTG.

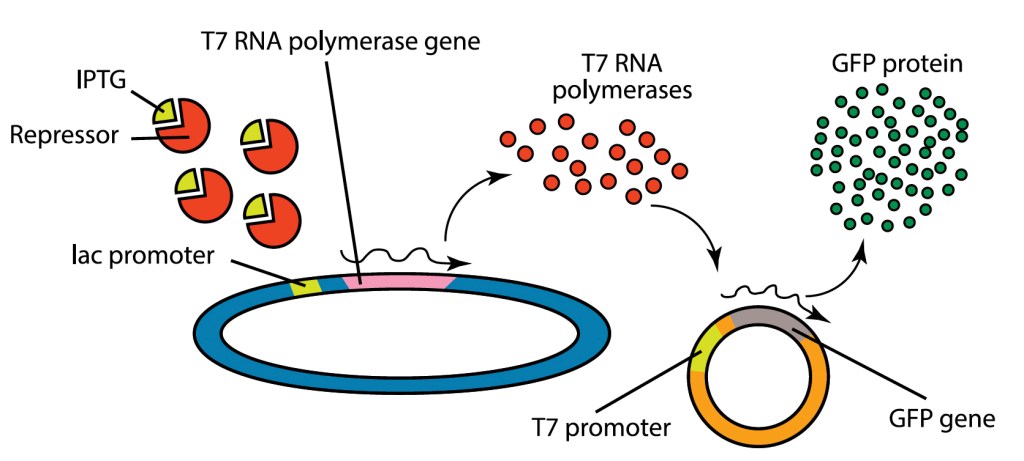

In our experiments, we use the lac operon as our genetic on/off switch. The lac operon is quite literally the textbook example of bacterial gene regulation (Figure 3). It acts like a switch that turns on or off depending on the presence of lactose. When absent, the lac repressor protein blocks gene transcription; when lactose binds to it, transcription is turned on, enabling the bacteria to break down lactose for energy.

Our transformation experiment involves genetically engineered host bacteria that express T7 RNA polymerase under lac promoter control. T7 RNA polymerase specifically binds to the T7 promoter that is found on the GFP plasmid that is transformed into the bacteria. Under normal circumstances, lac repressor binds to the lac promoter and blocks expression of the T7 polymerase, and cells will not fluoresce.

To turn on transcription, we will add IPTG, a molecule that mimics the structure of lactose and binds to lac repressor. This inactivates lac repressor, allowing T7 polymerase to be expressed and to recognize the T7 promoter found in the GFP-containing plasmid. This results in the transcription of large quantities of the GFP mRNA, which is translated to produce GFP protein , causing the cells to fluoresce.

What happens if I transfer cells that have expressed GFP to media that does not contain IPTG?

When IPTG is removed, the operon will turn off. At this point, the cells will no longer be able to produce new T7 RNA polymerase, or to transcribe more GFP mRNA.

However, there may be residual GFP activity left in the cells after the transfer. This is because it takes some time for new lac repressor to me made, and for the existing T7 polymerase and the mRNA to be degraded by the cells. During this time, more GFP protein can be produced. GFP protein is also very stable, and it can remain in the sample for a long time after it is produced. The protein still fluoresces brightly, even at low concentrations, so any remaining protein might be visible after introduction the cells into media that does not contain IPTG. The operon can also turn on if using a media that contains lactose, or in a media where the bacteria are starved and need to utilize alternative carbon sources. These considerations must be taken into account when performing the experiment.

How do I purify GFP protein?

After cells are transformed with the GFP plasmid, we can grow them in liquid culture that contains IPTG to produce large amounts of the protein. This media will contain IPTG to keep the lac promoter turned on, and antibiotics to prevent the growth of other bacteria in culture. In the case of highly active promoters, the target protein can comprise up to 70% of all proteins in a cell. Despite this high expression, the cells will still contain large amounts of additional proteins that must be removed. Choosing the correct purification method allows scientists to produce a quantity of pure protein, separated out from the rest of the cellular debris like DNA, organelles, and other proteins.

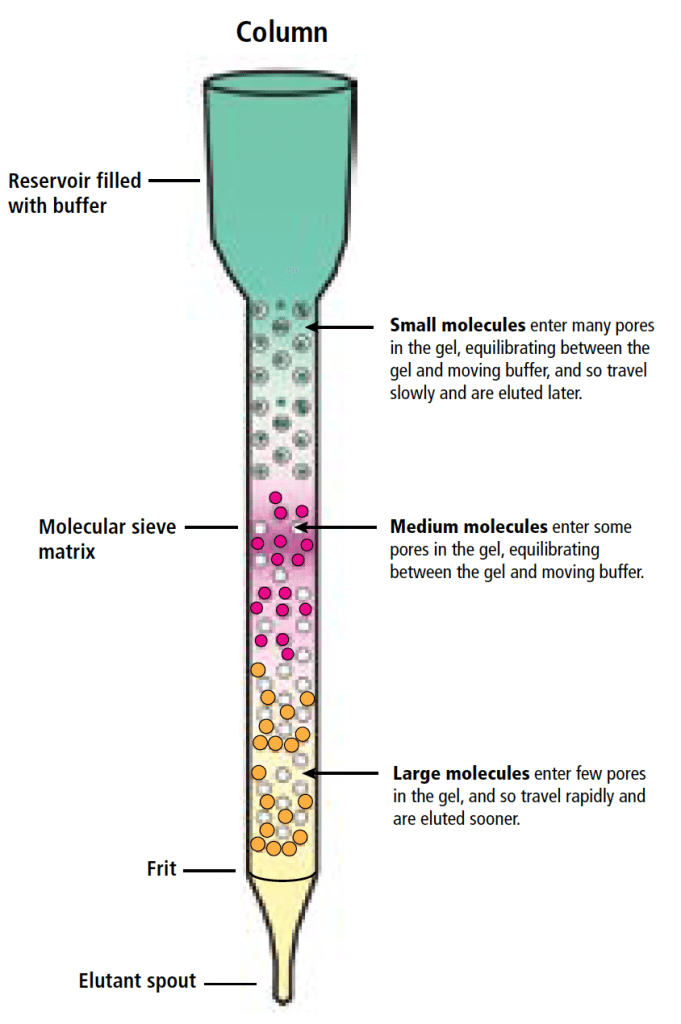

One of the most common methods for purification is to lyse the cells (that is, to break open the cells) and perform size exclusion column chromatography. The bacterial lysate is loaded into a long, narrow column filled with a size-exclusion matrix, a semi-solid material comprised of small beads that contains microscopic pores and channels. Larger molecules struggle to pass through the pores and instead flow around the beads, while smaller molecules navigate the maze of channels and pores more extensively. Consequently, larger, higher molecular weight proteins elute first from the column, moving more rapidly through the matrix. The samples are collected at the bottom of the column. Identifying the samples that contain GFP is easy – you’ll see them glowing green!

What allows our samples to continue glowing in the centrifuge tubes after they have been collected?

The fluorescence originates from the protein’s structure itself, not from being within the cells — no IPTG needed! The protein will persist in emitting light within the centrifuge tubes as long as its structure remains intact. However, if you boil the sample, like we do before running SDS-PAGE, GFP will no longer glow green! This is because the beta barrel structure of the protein is disrupted, and the chromophore is no longer formed. We can demonstrate this experimentally by comparing the native protein to the denatured protein — even before running SDS-PAGE, the native samples will glow, but the denatured ones will not.