Santiago Ramón y Cajal was a Nobel Prize-winning scientist and a founding father of neurology. However, he almost didn’t pursue a scientific career. Born in Spain in 1852, his spirited and determined behavior led to frequent school changes and even a few close calls. For example, at the age of 11, he was briefly imprisoned for destroying his neighbor’s gate with a homemade cannon! Fortunately, Cajal also had a passion for art and painting.

At 17, Cajal decided he wanted to attend art school. However, his father, a Professor of Anatomy at the University of Saragossa, had different plans. He eventually convinced his son to pursue a medical career by taking him to graveyards and allowing him to sketch bones!

After graduating from medical school, Dr. Cajal briefly served as an army doctor on an expedition to Cuba but contracted tuberculosis and malaria. Upon returning to Spain, he completed his doctorate and embarked on a career in teaching and research. He became particularly interested in histology—the study of tissues and organs through sectioning, staining, and examining them under a microscope.

Cajal’s initial research focused on epithelial cells, cholera, and inflammation. However, in 1887, he encountered a newly developed method for staining and visualizing neurons—the Golgi method. The intricate patterns quickly captivated both the artist and scientist in Cajal, prompting him to pivot to studying the brain and spinal nerves.

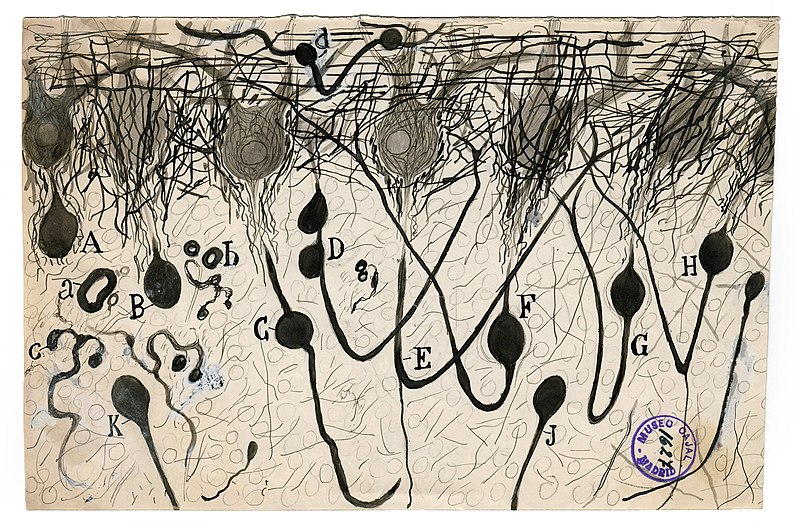

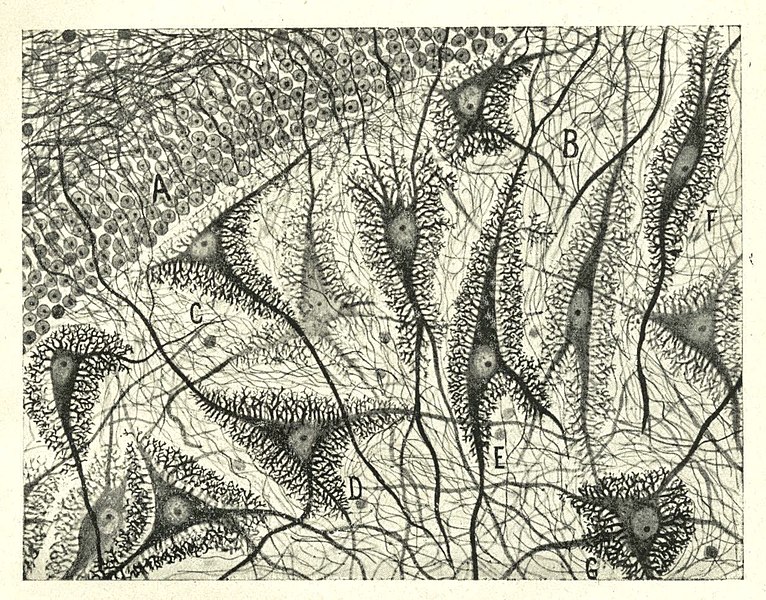

With his artistic training and passion taking center stage, Dr. Cajal created thousands of beautiful drawings depicting the intricate details of nervous tissue that he could now observe through his microscope. Armed with these observations and records, along with his insightful mind, Cajal gained profound insights into this key and complex human system.

Dr. Cajal proposed the special structure of neurons—a cell body, with one long projection (axon), and numerous little projections (dendrites). He also discovered axonal growth cones, ICC cells (interstitial cells of Cajal), and the spaces between neurons. The latter discovery led Cajal to develop the theory that the brain and spinal cord are composed of countless individual functional units, laying the foundation for the neuron doctrine. His idea that “the ability of neurons to grow in an adult and their power to create new connections can explain learning” is also considered the origin of the synaptic theory of memory. He also proposed and led research into the existence of dendrite spines, the role of electrical impulses within nerve networks, and the polarization of nerve cells. In 1906, Cajal was jointly awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his assertion that the brain is composed of individual neuron cells rather than a single continuous network.

Cajal’s art deeply influenced his science. His keen artistic eye enabled him to penetrate the intricate patterns and structures of nerves, long before the advent of electron microscopes. These dynamic and detailed illustrations served as invaluable tools, allowing him to record, visualize, and comprehend the complexities of the brain. Even today, Cajal’s drawings serve as a wellspring of inspiration, gracing art exhibitions worldwide and adorning the offices and desks of countless neuroscientists.

The potent fusion of science and art perhaps may also (partially) explain Dr. Cajal’s enduring passion and insatiable curiosity. In 1922, at the remarkable age of 70, he established the Laboratorio de Investigaciones Biológicas, a pioneering research center dedicated to neurobiology. Renamed the Cajal Institute, it remains a cornerstone of cellular and molecular neurobiology, neuropharmacology, electrophysiology, systems neurobiology, and neuropathology. Even on his deathbed on October 17, 1934, Cajal persisted in his pursuit of discovery, a testament to his unwavering dedication to unraveling the mysteries of the brain.

1 comment

Comments are closed.