It started with a mystery and then a high-tech search.

In the 1990s, Dr. Jonathan Zehr, an ocean ecologist at the University of California, found an eye-catching DNA sequence in the water samples he was studying. Analysis of the sequence suggested that the organism it belonged to had a rare and powerful function—the ability to take nitrogen gas from the environment and turn it into proteins and DNA. This process is known as nitrogen fixation.

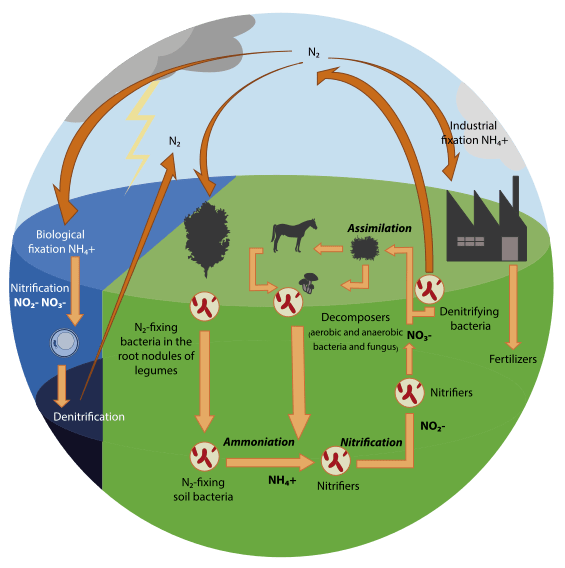

Nitrogen fixation is a critical ecological process that ensures living organisms get an essential nutrient. Unfortunately, there are only a few ways to accomplish it. Lightning has the energy to convert atmospheric nitrogen, N₂, into a usable form like nitrates. A handful of organisms contain the enzyme nitrogenase, which can break apart and convert N₂. These include symbiotic bacteria like Rhizobium and Actinobacteria, cyanobacteria, and a few free-living species of archaea and bacteria. Finally, we developed the Haber-Bosch process in the early 20th century—an industrial method for producing ammonia for fertilizers—and it remains a cornerstone of modern agriculture.

To understand more about the new nitrogenase gene, Dr. Zehr analyzed it from an evolutionary standpoint. By examining the gene’s unique nucleotide sequence the team concluded that it likely came from a highly distinct nitrogen-fixing microbe, sparking even greater interest in this mysterious organism.

However, when scientists searched for this microbe under the microscope, they couldn’t find it. The sequence appeared in all types of ocean water—tropical, arctic, open ocean, and coastal—but no one could locate the organism. Even after examining countless gene-positive water samples with high-powered microscopes, they found nothing. In the end, they named the mystery organism Unicellular Cyanobacterial Group A, or UCYN-A for short. Cyanobacteria are among the most abundant organisms to have ever existed and are also one of the few that can perform nitrogen fixation – so overall it was a good guess!

The next breakthrough in the case was a new hypothesis. Since many nitrogen-fixing organisms are symbionts—organisms involved in close, long-term relationships with another species—Dr. Zehr and his colleagues started wondering if UCYN-A might be one of them.

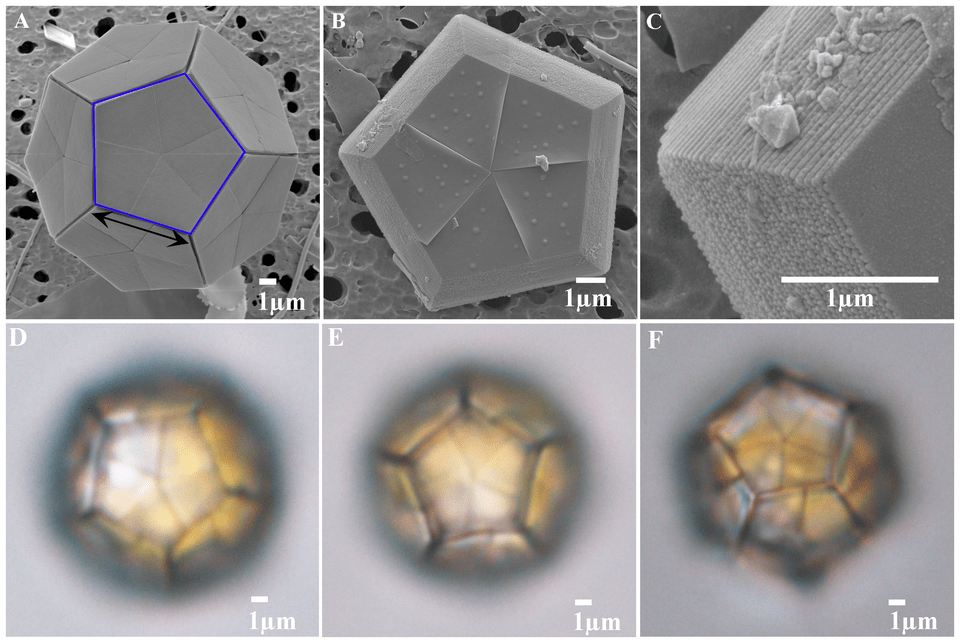

The symbiont hypothesis turned out to be a game-changing clue. The team discovered that a single-celled algae called Bramarudosphaera bigelowii was associated with and quite possibly helping UCYN-A. But B. bigelowii threw them a new curveball. The species proved nearly impossible to raise in the lab. Nearly, but not impossible. Dr. Kyoko Hagino, a marine biologist at Kochi University, spent over 12 years trying to culture these single-celled, marine, calcifying algae that look a lot like soccer balls. She finally cracked the code by adding new ingredients to the culture media.

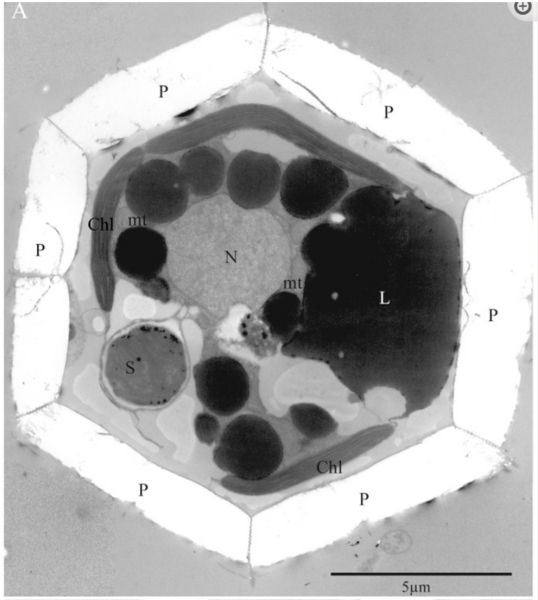

With a lab-ready system finally in place thanks to Dr. Hagino’s work, scientists were set to study B. bigelowii and UCYN-A together. One of their approaches was to peer inside the cell using transmission electron microscopy (TEM). This powerful imagining technique uses electron beams instead of light to visualize specimens at incredibly high resolutions. In this case it allowed them to see inside living B. bigelowii cells at an unprecedented magnification.

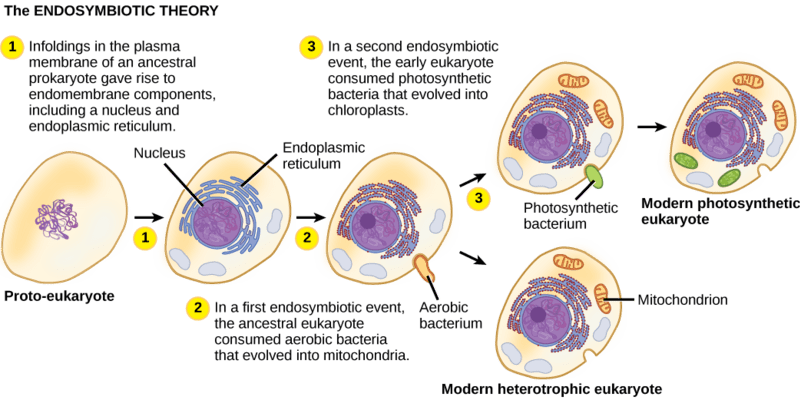

And that’s when they finally found it! After nearly two decades of searching, inside each B. bigelowii cell was what looked like another tiny cell that they could link to their nitrogenase gene. This seemed like a clear case of endosymbiosis—a symbiotic relationship where one organism lives within the body (or cell) of another. But endosymbiosis isn’t always the end of the story. The endosymbiotic theory suggests that some organelles evolved from free-living bacteria that entered into endosymbiotic relationships with ancestral eukaryotic cells but, over time, became fully integrated as organelles. Such a transition from endosymbiont to organelle represents a continuum. Still scientists wondered which were they observing?

To decide, they looked at key areas that can distinguish the two. These include:

– Genetic independence: endosymbionts retain more of their original genome, while organelles have transferred most of their genes to the host nucleus.

– Growth: endosymbionts can grow at a different rate or time than their host, while organelles tend to grow in synchrony with their host.

– Reproductive autonomy: endosymbionts often reproduce independently, while organelles typically replicate under host cell control and are inherited during the host cell’s division.

Genetic analysis had already shown that UCYN-A lacked most genes essential for life. In addition, proteomic research showed that many proteins in UCYN-A are are encoded in and imported from B. bigelowii. Research into the size ratio of UCYN-A and B. bigelowii also show near synchronous growth. Finally, researchers studying the cell divisions of both organisms observed that when B. bigelowii cells divided, the UCYN-As within those cells also divided and were passed down evenly to both daughter cells. It was clear that a new name was needed. No longer considered an organism (and hard to say anyway) UCYN-A was scrapped and replaced with nitroplast.

The discovery of the nitroplast marks a groundbreaking breakthrough with far-reaching implications for evolution, ecology, and agriculture. Scientists have hailed it as “one for the textbooks” and even “the holy grail” of biological discoveries. Nitroplasts provide new insights into the fundamental evolutionary process of organellogenesis—the transformation of free-living organisms into organelles. This process gave rise to chloroplasts and mitochondria, making it a cornerstone of eukaryotic cell history. The evolution of nitroplast offers a fresh and relatively recent (~100 million years ago!) example.

Because Nitroplast are found in diverse ocean samples and because they play a crucial role in nutrient cycling, its discovery could also have significant implications for marine ecology.

Finally, B. bigelowii with nitroplast represents the first known case of nitrogen fixation in a eukaryote—a function previously thought to be exclusive to prokaryotes. This discovery raises intriguing questions: Could nitroplasts exist in other organisms? Could they be introduced into new species? Exploring alternatives to synthetic nitrogen fertilizers could enhance crop productivity, improve farmers’ economic outcomes, and mitigate some of the most significant environmental impacts of agriculture. The discovery of the nitroplast opens a new avenue of research and the potential to develop plants capable of fixing their own nitrogen.

Explore the full details of this discovery in the following scientific articles:

Or, if you’re in a biology classroom, explore these (and similar) concepts and tools firsthand with the following experiments :

The Mother of All Experiments: Exploring Human Origin by PCR Amplification of Mitochondrial DNA