One of my favorite ways to design new experiments for Edvotek is to be inspired by real world biotechnology news. We’ve released kits talking about vaccine development, genetic cures with CRISPR, and disease detection using the ELISA. A recent use of biotechnology that I find particularly interesting is the use of wastewater testing to detect diseases in a community. By using biotechnology to analyze sewage, public health officials can detect harmful bacteria and viruses before outbreaks occur.

But how does this work?

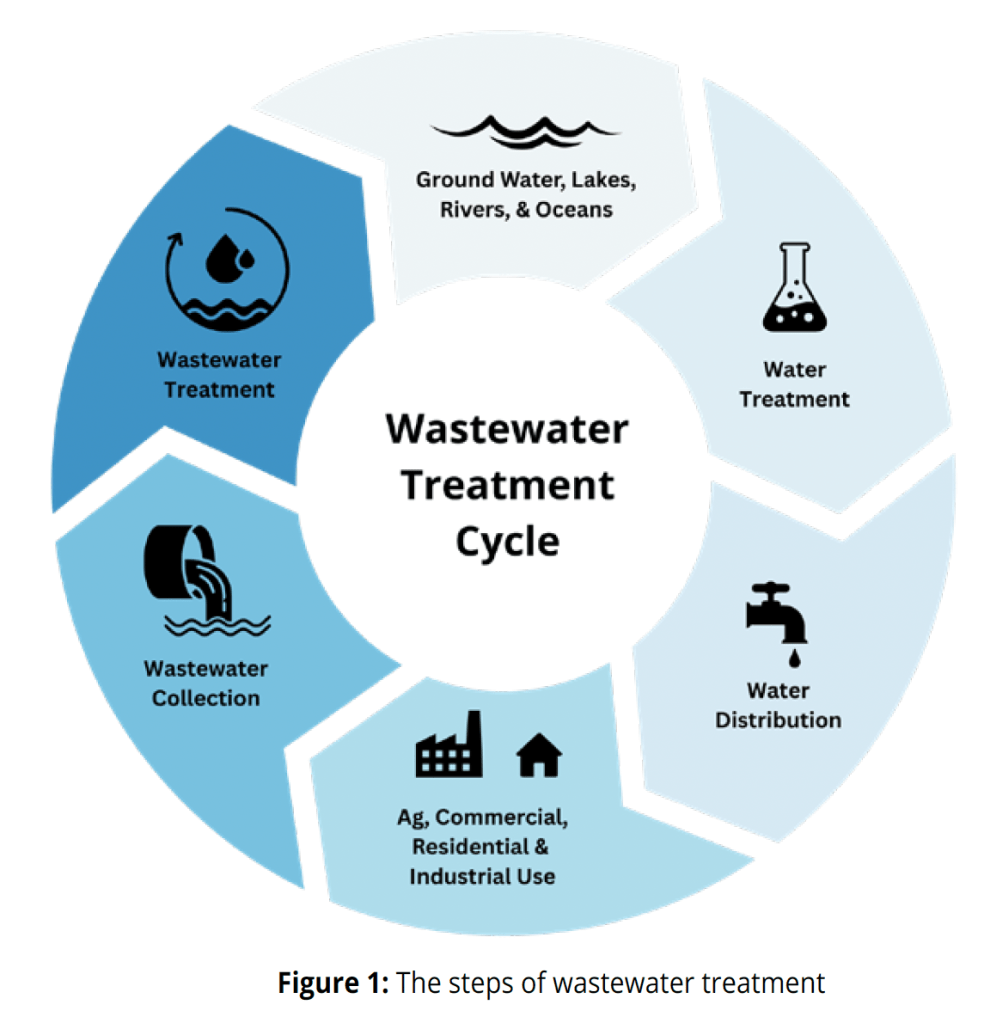

In simple terms, wastewater is the used water that flows out of our homes, schools, businesses, and farms. Because it has been used, it can contain a wide variety of substances that are not healthy for human consumption. This can include food waste, fertilizers, chemicals, and yes — everything and anything that has been flushed down the toilet. Before this wastewater can be released back into lakes, rivers, and oceans, it must be collected and made safe at a wastewater treatment facility (Figure 1). This includes removal of debris from the wastewater, filtering of sediment, elimination of contaminants, and disinfection to prevent the spread of diseases.

Since wastewater carries human waste, it contains bacteria and viruses shed by sick people in the community. By using molecular tests to identify the presence of these pathogens in the water samples, public health officials can detect diseases in a community before people even start showing symptoms. This method has been used to track diseases like COVID-19, polio, norovirus and E. coli.

The first step in wastewater testing is sample collection. Scientists collect wastewater from key sites like municipal water treatment plants, university dorms, or even cruise ships — anywhere where there are a large number of people and the potential for illness.

The next step is to identify potential pathogens in the sample. That’s where biotechnology comes in! Most times, scientists use quantitative polymerase chain reaction, or qPCR, to detect bacterial and viral genetic material. qPCR works by taking tiny amounts of the pathogen’s genome and copying it billions of times.This technique is incredibly sensitive, allowing scientists to detect even the smallest traces of a pathogen in wastewater.

If the pathogen is present, epidemiologists and public health departments plan their next steps to contain potential outbreaks. One of the biggest advantages of wastewater testing is that it allows public health departments to get ahead of potential outbreaks. People can start shedding viruses or bacteria in their waste before they show symptoms—sometimes up to a week in advance!

Inspired by this biotechnology innovation in public health, we began to design an experiment that would be fast and reliable in your classroom and — more importantly — safe! In our new kit, “Follow That Flush”, your students take on the role of public health scientists investigating a potential outbreak of gastrointestinal disease in Pinehurst Ridge. After receiving reports from local doctors’ offices, they collect wastewater samples from key locations across the city. Students work through concepts in PCR and gel electrophoresis to detect the presence of bacterial or viral pathogens in their samples. Importantly, this kit is a simulation, meaning that your students will not come into contact with any pathogens that could affect their health.

We have designed multiple educational resources to help you teach this lesson about disease detection and prevention, including videos, powerpoint slides, career resources, a detailed real-world scenario, and a new FREE interactive e-learning module! Through this virtual investigation (complete with some escape-room style puzzles), students learn how biotechnology tools like wastewater testing are used to track disease and protect public health. Try it out and let us know what you think!

This project was made possible by a Science Education Partnership Award (SEPA), Grant Number 2R44GM143977-02, from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH).