Gene cloning is a cornerstone of modern molecular biology, enabling the study, manipulation, and engineering of genetic material. For science teachers and advanced students, a thorough understanding of various gene cloning strategies is essential for both foundational knowledge and for engaging with current research. Here we will take an in-depth look at three widely used methods—Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR), Traditional Restriction Enzyme-Based Cloning, and Golden Gate Assembly—emphasizing mechanisms, technical strengths, limitations, and comparative applications.

Traditional Restriction Enzyme-Based Cloning

This classical method, foundational to recombinant DNA technology, utilizes restriction endonucleases to cleave DNA at sequence-specific sites, often creating “sticky” (overhanging) or “blunt” ends. Subsequently, DNA ligase facilitates covalent linkage of insert and vector DNA, generating recombinant plasmids or other vectors.

- Mechanism: The target gene is excised from a source by restriction digestion, and the vector (commonly a plasmid) is linearized with compatible enzymes. Digested DNA fragments are purified and ligated, after which transformation into Escherichia coli (or another host) yields recombinant clones.

- Design Considerations: Selecting unique restriction sites flanking the insert is critical; sometimes synthetic linkers or adapters are used. Directional cloning (using two different enzymes) prevents insert inversion.

- Applications: Generation of expression constructs, library construction, and gene knock-out/in strategies.

- Limitations: Restricted by the presence and distribution of enzyme recognition sites. Multiple or incompatible sites may necessitate additional engineering, and the process can be labor-intensive and relatively low-throughput.

Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR)

PCR, developed by Kary Mullis in 1983, is a robust and highly sensitive technique that enables exponential amplification of a specific DNA segment. The method has proven indispensable not just for research but also for medical diagnostics, forensics, and evolutionary biology. Central to PCR is the thermostable DNA polymerase (e.g., Taq polymerase), which extends DNA synthesis across cycles of high and low temperature, guided by user-defined oligonucleotide primers.

- Mechanism: The reaction involves three primary steps: denaturation (typically 94–98°C), annealing (primer binding at 45–65°C, sequence-dependent), and extension (DNA synthesis at 72°C). This cycle is repeated 25–40 times, resulting in the geometric amplification of the target DNA region.

- Design Considerations: Primer design is crucial for specificity and efficiency. Primer-dimers, secondary structures, and GC content must be optimized.

- Applications: Amplifying genes for cloning, mutagenesis via site-directed PCR, quantitative PCR (qPCR) for expression studies, and more.

- Limitations: PCR does not directly enable insertion into vectors, and high-fidelity enzymes may be required to avoid sequence errors. Amplified fragments must be further processed for downstream molecular work.

Golden Gate Assembly

Golden Gate Assembly is an advanced, modular method that exploits Type IIS restriction enzymes, such as BsaI or BsmBI, which cut DNA outside their recognition sequence. This property allows the creation of user-defined overhangs, enabling seamless, directional, and scarless assembly of multiple DNA fragments in a single tube and reaction cycle.

- Mechanism: DNA fragments are designed with flanking Type IIS enzyme sites so that after digestion, the resulting overhangs dictate the precise order and orientation of assembly. The reaction mixture includes both the restriction enzyme and T4 DNA ligase, allowing concurrent digestion and ligation at an isothermal temperature (usually 37°C). The method can assemble upwards of 10 or more fragments simultaneously.

- Design Considerations: Careful sequence design is required to avoid internal Type IIS sites. Overhangs must be unique and compatible, which can be managed using specialized software or manual curation.

- Applications: Complex pathway engineering, synthetic gene circuit construction, rapid assembly of modular vectors, and library generation.

- Limitations: Sensitive to sequence context (internal enzyme sites may require removal by synonymous mutation), and success depends on high-quality oligo/DNA preparation.

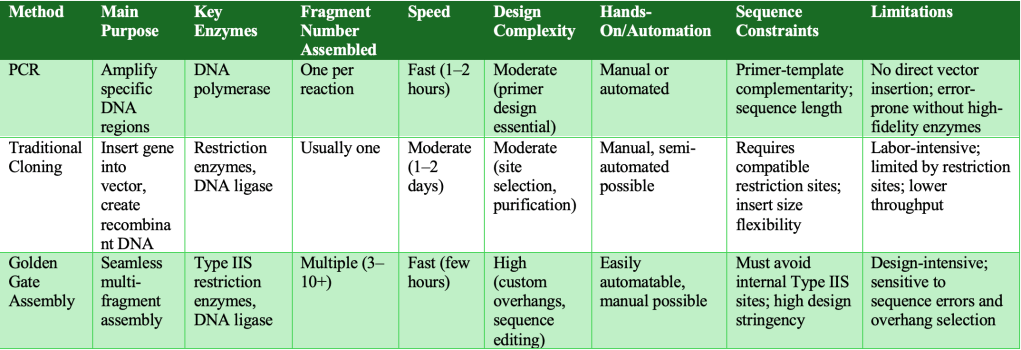

Comparative Analysis: PCR, Traditional Cloning, and Golden Gate Assembly

The table below provides a more technical comparison of these gene cloning methods, highlighting mechanistic, practical, and design aspects relevant to experimental planning and classroom demonstration.

Takeaways for Teaching

Each gene cloning method has distinct advantages and challenges. PCR is foundational for amplification and targeted mutagenesis but is not a true cloning technique until combined with vector insertion strategies. Traditional restriction cloning, while robust and widely taught, is increasingly supplemented or replaced by more flexible and scalable methods. Golden Gate Assembly exemplifies the power of modern synthetic biology, allowing rapid, precise, and high-throughput construction of genetic elements.

For educators, demonstration or discussion of these approaches can highlight core concepts such as enzyme specificity, the importance of sequence context, and the evolution of laboratory techniques. Hands-on activities like designing primers, modeling restriction digests, or exploring the assembly logic of Golden Gate connect theory to practice, and prepare students for advanced studies or laboratory work.

I hope you enjoyed this cloning review! Interested in experimenting with PCR or Traditional cloning? Check out Kit 301: Construction and Cloning of a DNA Recombinant, Kit 330: PCR Amplification of DNA, or Kit 300: Blue/White Cloning of a DNA Fragment & Assay of ß-galactosidase.